The rubber is finally meeting the road for the transition to green energy, perhaps nowhere more so than on the US West Coast. Two years ago, California announced its plan to reach full carbon neutrality (“net zero”) emissions by 2045, and Washington has set an only slightly less ambitious target of 95% emissions reduction by 2050. For its part, Oregon has committed to 100% carbon-free electricity by 2040. Huge buildouts of renewable power are rapidly needed to meet these targets, yet expanding large solar and wind farms on land meets resistance because they cover so much territory. So government and private industry have also turned their attention to offshore wind, which the West Coast has in abundance. A study by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) concluded that the highest wind speeds and greatest offshore wind potential in the country are found directly off the Northern California and Southern Oregon coasts. Other work from Energy Innovation and partner groups showed that, nationwide, offshore wind could provide up to 25% of US electricity production by 2050.

The benefits of offshore wind are legion. Offshore winds are consistently strong, and the turbines can be built significantly larger than their on-shore counterparts. Both of these elements help make the capacity factor of offshore turbines (the fraction of time electricity generation is turned on) up to twice as high as more intermittent onshore wind or solar farms, and comparable to natural gas power plants. Because electricity is provided for a much higher fraction of the time, offshore wind does a great job of complementing on-shore generation over both hourly and seasonal timeframes, making it easier to meet peak demand on the grid while also reducing the amount of expensive battery storage needed. This is particularly important given that reduced snowpack from climate change and removal of some large dams will likely diminish the contribution of hydroelectric power.

No wind farms operate yet off the US West Coast. Nonetheless, bringing existing plans to fruition is a matter of great urgency in the battle against climate change – especially given expected increases in power demand coming from electrification of end uses in homes, businesses, industry, transportation and AI data centers. Fortunately, offshore wind’s benefits extend beyond providing clean and affordable power as a fundamental part of decarbonizing the economy. The technology will also enhance the reliability of the overall electricity grid, and create tens or even hundreds of thousands of sustainable, family-wage jobs, bolstering economies of shoreline communities around the country.

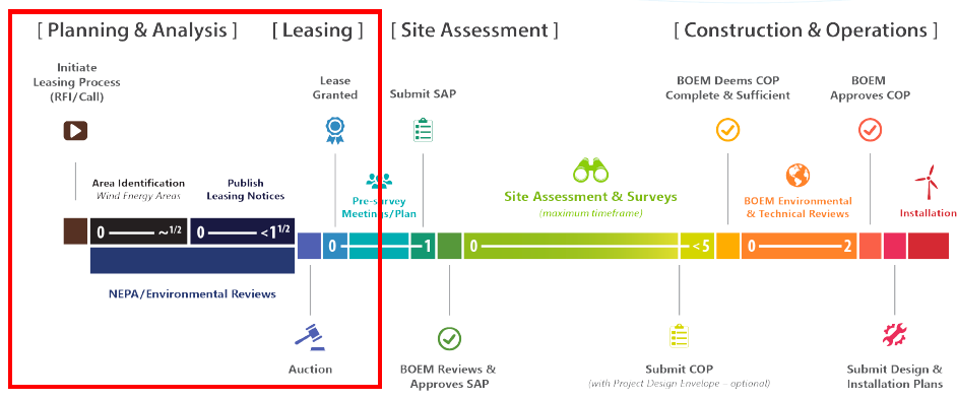

Perhaps the most challenging aspect of US offshore wind projects is that they take a decade or more from conception to fruition. The figure below, provided by the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, shows a typical timeline:

Key aspects of the process are in the hands of the federal government, because offshore wind farms are built in federal waters farther out from the coastal strip, 3 nautical miles wide, within which East and West Coast states have jurisdiction. In the early stages, depicted inside the red box at left, BOEM initiates the leasing process by putting out a Request for Interest to collect information on which private firms might become involved. Relying on large amounts of scientific data from NREL and other groups, BOEM also identifies key Wind Energy Areas where turbines might ultimately be located. The Lease Areas subsequently offered in an auction then comprise smaller units of offshore land within the wind energy areas. Finally, in these early stages BOEM also leads environmental reviews of potential projects under the National Environmental Policy Act, focusing on ecological impacts on lease areas as well as disruption to human and natural systems that occur while building connecting electric transmission lines and onshore support facilities.

These early stages last at least several years, although they are taking longer on the West Coast because the technology is very new and a great deal of stakeholder education has been needed. In fact, Pacific waters are so deep that the turbines cannot be pipe-driven into the sea floor, as is possible for turbines located in shallow waters on most of the East Coast. Instead, West Coast offshore wind generation requires the use of floating technology, where turbines are mounted on buoyant platforms and attached to the ocean floor with mooring lines and anchors.

A key commitment point in the BOEM process is the lease auction, where companies bid for the right to build the projects. The size of the bids can be very large: in 2022, an offshore wind auction held in New York state resulted in winning bids totaling $4.37 billion, the most ever paid for an offshore energy lease, including any offshore oil or gas lease awarded in the past four decades. Clearly these projects are enormous commitments for private firms to take on.

The lease auction occurs near the beginning of the ten-year approval process, so the developer has to pay up before BOEM begins most of the environmental, technical and construction plan reviews (see the Figure). This makes it important for state proponents to create an environment where privately held developers and their investors feel secure enough to take the risk, as mere acquisition of a lease does not guarantee that a project will be successfully built. Environmental and other issues implicated by offshore wind development are legitimate, but stakeholders with such concerns, including the fishing industry, should note that there are many opportunities to also become involved after the leases are awarded. These range from the site assessment plan (SAP; see the Figure) near the beginning of the process, to the construction and operation plan (COP) that comes after all the site work and surveys, to the final review stages. More opportunities for public input come at the state and local levels, since further permitting and review also takes place in those parts of government.

The pace of offshore wind development is not the same in the three West Coast states. Washington has yet to make a real commitment to the industry, while California is well out in the lead. Three years ago, the California legislature passed Assembly Bill 525, requiring state agencies to develop a strategic plan for offshore wind. In response, the California Energy Commission adopted a roadmap to generate 25 gigawatts (GW) of electricity from offshore wind by 2045 (for comparison, the state had a total electricity generation capacity of 83 GW in 2021). That plan envisions up to 26 ports along the coast along with a dozen industrial sites for fabrication. Two other recent bills, the Offshore Wind Expediting Act (SB 286) and California Offshore Wind Advancement Act (AB 3), reduce permitting timelines and provide more certainty for developers and investors. In 2022, BOEM awarded the first offshore California leases to five different private developers, three on the central coast and two in northern Humboldt county. Finally, in a showing that success begets success, earlier this year the US Department of Transportation awarded a $426 million grant to the Humboldt Bay Harbor District to build a new marine terminal in support of the anticipated offshore operations.

If California appears fully committed while Washington has yet to get going, Oregon occupies a middle ground. In 2019, BOEM convened an intergovernmental task force to look at the Oregon offshore resource, with over 100 stakeholders from federal, state, local and tribal governments. The meetings also included commercial fishing, environmental groups, and representatives from other business and organized labor communities. This has created a robust record of public engagement, yet resistance remained from Governor Kotek and four members of Oregon’s Congressional delegation, who requested last year that BOEM pause the approval process to more fully evaluate effects on the environment and economy. This request was echoed by the Oregon Coastal Caucus, a group of state legislators representing the coast counties, who also requested that BOEM take further steps to consider the concerns coming from fishers. Fortunately, experiences with offshore wind elsewhere, especially off Europe’s Atlantic coast, have revealed little evidence of adverse impact to commercial fishing – and in some cases have even given rise to positive “reef effects” whereby the abundance and variety of some species is improved.

Most recently, the prospects for Oregon offshore wind have improved. In March, the Oregon legislature passed a bill, HB 4080, which declares a state policy to support engagement between offshore wind developers and impacted organizations, communities and tribes. This sets up a roadmap to address the concerns expressed by Governor Kotek and some members of the state legislature. HB 4080 includes mandates for fair labor standards for the construction and manufacturing of component parts, and for hiring of new agency staff – provisions that may help win over some key constituencies. In addition to signing off on HB 4080, Governor Kotek has further stated that her office recognizes both the opportunities and risks of offshore wind development. This is not exactly a ringing endorsement, but at least does not suggest that she will try to block next steps in the development process.

And the next step in Oregon is a very big one. Over the past few years, the initial steps in BOEM’s process for Oregon’s offshore wind development have been executed. Two lease areas have been identified, one close to the California border where power production could connect to planned Humboldt county facilities, and a second about 100 miles to the north. Environmental assessments have been completed, and the initial canvassing of interest has generated responses from at least four private firms. All eyes are now on the BOEM auctions for Oregon’s first two lease areas, which are expected in October. The full impact of the public engagement process, and the reality of continuing opposition from some local interests and state legislators, will likely not become clear until we see the bid amounts that developers are willing to put at risk. This upcoming auction is critical, because BOEM’s projected leasing schedule suggests that another may not be held until after 2029.

Private firms bidding for development rights can look forward to robust revenue streams from those strong offshore winds, but they are also keenly aware of delays and cancellations of some East coast projects arising from problems with materials supply chains, delays in financing and macroeconomic impacts such as high interest rates and inflation. Nonetheless, there are some good reasons to be optimistic in the Oregon case. US federal tax credits for wind and other renewable energies used to be notoriously fickle, but the Inflation Reduction Act now reliably extends both production and investment credits until at least 2032, long enough to see new projects through. Another advantage is that the Oregon transmission grid can already integrate up to 2.6 GW of offshore wind power (the equivalent of several good-sized offshore projects) without major upgrades. This helps relieve one of the major barriers that has caused difficulties for other offshore wind projects. In general, Oregon and other West Coast offshore wind projects also benefit by learning from the experience of successful East Coast ventures that have overcome these challenges.

HB 4080, the new Oregon law supporting offshore wind development, may help spur the incorporation of Community Benefit Agreements into lease agreements that emerge from the auctions. CBAs are voluntary, but can help ensure offshore wind creates economic opportunity and equitable development by providing up to 30% of the lease bid amounts for workforce training, supply chain development, etc. BOEM has incorporated bidding credits into the auction process for developers willing to incorporate CBAs as legally binding parts of the leases, as in the successful California auctions two years ago. These may go some distance towards overcoming the remaining concerns in Oregon coastal communities. Power purchase agreements made with regional electric utilities have also been included in leases for successful BOEM auctions held in Maryland, Massachusetts and Rhode Island. This is also an option.

Finally, it is very much worth noting that the Pacific Northwest has recently been successful in attracting federal funds for a Green hydrogen hub to spur development of electrolytic methods for synthesizing clean hydrogen from water. The biggest barrier to green hydrogen is the large amount of electricity needed to drive the electrolysis process – and to avoid overburdening the existing grid, this power should come from new sources. Offshore wind and green hydrogen thus look very much like a match made in heaven. It is exciting to see these two key elements of the post-fossil fuel economy emerging together here in Oregon. As healthy climate advocates, we should do whatever we can to help make this all a reality.