It’s past time that we take a fresh look at the state of Earth’s climate. I had planned to write this last month, but new analyses of what happened in 2024 kept appearing in the scientific literature and popular press. So this piece will include some very recent expert opinion about how to interpret last years’ record-breaking global warming. Last winter, I wrote that the outcome for 2023 was hard to see in a positive light. Update “hard” to “impossible,” and you will get the sense of what the data say about 2024.

Like last year, I will offer a brief survey of the key findings as reported by US federal agencies (NOAA and NASA), an academic think tank (Berkeley Earth), the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), and numerous other groups – all ably synthesized by Zeke Hausfather at the invaluable climate journalism site CarbonBrief. We will then look at possible explanations for the temperature data, including an influential article that appeared last week from Jim Hansen and his team. After digesting all this, we will have more than earned the right to look on the bright side, so I will close by highlighting a few 2024 events that offer a more hopeful perspective.

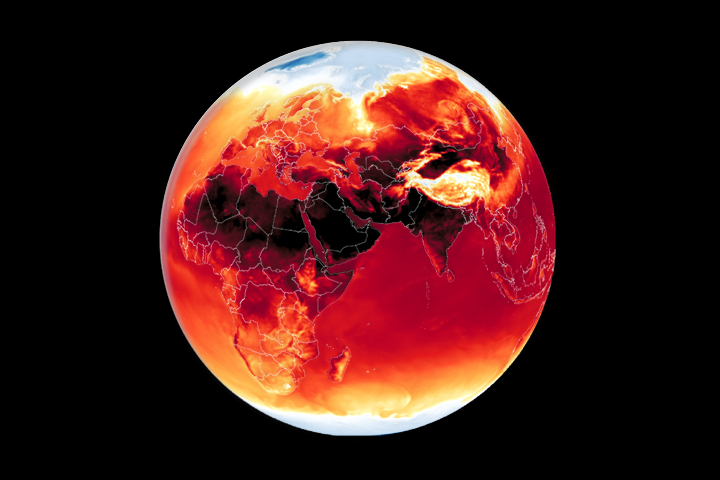

All of the temperature datasets show that 2024 was the warmest year since modern record keeping began. Overall surface temperatures were 0.11°C warmer than for 2023 – which had, of course, been the previous record setter. That jump of over 0.1°C within one year is unprecedented. Both 2023 and 2024 were more than 1.5°C hotter than preindustrial temperatures, with the range for 2024 (over seven independent datasets) coming in at 1.46 – 1.62°C.

The Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C target is interpreted over a 20 year period, so even two years exceeding that level do not yet mean we have crossed the line. Nonetheless, the extraordinary warming of the past two years suggests that we may well surpass this milestone before the present decade is out. In its mid-January report, CarbonBrief does project (with large uncertainties) that 2025 will come in a bit cooler than the past two years, though still warmer than all prior years. Yet the data for last month, reported this week by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), show that Earth has just experienced the warmest January ever recorded.

The 2023-2024 temperature spike is not well understood. One factor was certainly the 2023 El Nino climate pattern over the Pacific Ocean, a well-known natural climate variation that leads to a temporary increase in overall surface temperatures over a period usually lasting about nine months to a year. This time, the El Nino was exceptionally strong. Further, unlike the last strong El Nino event in 2015-2016, temperatures failed to decrease as expected in 2024. So something else is clearly going on. However, the climate science community has not settled either on why the 2023 El Nino was so strong, or on why the heat persisted and even increased through 2024.

The most benign explanation for the first question is that the sharp temperature spike associated with this particular El Nino event could have resulted entirely from natural variation. In a paper published four months ago, a team of six American researchers showed that the chances of such an extreme spike increase significantly if the immediately preceding La Nina cooling happens to be especially prolonged. That was indeed the case this time. The team was able to reproduce the temperature spike in their models without including human influences. This does not negate anthropogenic global warming generally, of course, but does show that within the overall warming trend, natural factors could explain why the 2023 El Nino was so severe. However, this paper did not address why the temperatures increased further in 2024, instead of going down as expected.

The other two possible explanations are much more worrisome. At the annual December meeting of the American Geophysical Union, a team of German climate scientists presented an analysis of satellite data that has been measuring Earth’s cloud cover for over 20 years. Their paper shows that low cloud cover over parts of the tropics and the Northern hemisphere has been slowly decreasing. Because these clouds reflect solar radiation, their slow loss means that more heat is entering the climate system. As explained in the CarbonBrief analysis, the researchers do not know why the cloud cover is shrinking, but anthropogenic influences are probable. Their analysis is important because – if confirmed by other scientists – it would close a persistent gap between observed warming and many climate model projections, which underestimate the temperature increase by about 0.2°C.

This brings us to Dr. Jim Hansen’s analysis. Many groups have pointed to the possibility that the recent global warming spike could be due to better pollution control. The most obvious cause is the recent adoption of sulfur-free diesel fuel for ocean shipping, as mandated by the International Maritime Organization. Burning the cleaner fuel generates far fewer sulfur aerosols, which cool the Earth’s surface by reflecting solar radiation. The sharp decrease in these aerosols then unmasks the global warming that was already present.

A key connection between these studies is that anthropogenic aerosols in the atmosphere also help to seed cloud formation. Dr. Hansen argues that most global climate models employ an unrealistically small aerosol effect, thus producing less projected warming when aerosol levels are decreased. In particular, he thinks that the aerosol effect on clouds is nonlinear – when there is a lot of aerosol, then small decreases do not affect cloud formation much. But when the total quantity of aerosols in a part of the atmosphere is lower, the effect of a further small decrease in their concentration is amplified. This could be enough to contribute to the decreased low cloud cover seen in the satellite analysis. The consequent lowering of Earth’s reflectivity then helps create today’s record-breaking heat.

Dr. Hansen goes further by showing how underestimating the aerosol effect leads the most popular climate models – those used by the IPCC – to also lowball Earth’s climate sensitivity. This means that the temperature increase for a given level of greenhouse gas emissions could be higher than many experts think. I wrote last year about how Hansen’s findings are resisted by some climate scientists because they sharply challenge the status quo. But the remarkable warming of the past two years should be reason enough to take his results seriously. If measurements of sea surface temperatures remain anomalously high through 2025, it will indeed strongly suggest that we have entered an era of accelerating climate change, as Hansen argues.

In the last part of his paper, Dr. Hansen takes a slightly more optimistic view, writing that the slow response of the Earth’s climate system allows us some space to act with urgency to counter the threat. The past few months have given us both Hurricane Helene and the devastating California wildfires, both clearly catalyzed by anthropogenic warming. These events may catalyze, in turn, a tipping point in the hearts and minds of many Americans, who want to act before the physical tipping points in the climate system are breached.

So, what is the more hopeful news from 2024? In the US, we continue to see dramatic growth in renewable energy, paralleling similar trends in the European Union. New installations of solar, wind and battery power surpassed all previous records last year, showing a 47% increase over the already impressive additions in 2023. And just in 2024, China added more new solar power than the total present solar capacity of the entire US. Although there is concern about China’s continued reliance on coal, that should not distract us from this remarkable achievement: the country has reached a plateau in its CO2 emissions five years ahead of predictions made in the last decade. As China is by far the world’s largest emitter, this accomplishment means that global emissions, too, are reaching a plateau.

The annual international climate meeting, COP29, took place in Baku, Azerbaijan at the end of November. A charitable summary is that the meeting did not live up to expectations. Certainly it had none of the drama of COP28, with its Global Stocktake progress report and last-minute triumphalism about the (possible) demise of fossil fuels. But one accomplishment does stand out: an accord on implementing Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, addressing market-based mechanisms to foster international collaboration on emissions goals.

In UN jargon, “CMA” means the governing body that is responsible for translating the 2015 Paris Agreement into action. At Baku, after nine years of effort, the CMA finally adopted rules and procedures for two key initiatives. Article 6.2 allows countries to enter bilateral agreements to trade on their nationally determined contributions (NDCs) – their plans to reduce emissions and remove carbon from the atmosphere. And Article 6.4 sets up a new mechanism to issue and verify high-quality carbon credits.

Article 6.4 is a big deal because it sets up a global-scale voluntary carbon market under UN auspices. This new Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism replaces the Clean Development Mechanism that has been in effect until now. The new UN market will function separately from the already-existing voluntary carbon market, a loosely knit system lacking strong central direction. The hope for Article 6.4 is that it will bring order to the marketplace, set high standards for verification, and establish a pricing scale through which well-verified and durable carbon sequestration projects fetch the highest prices per ton. The Baku agreement now sets up a process for establishing standards by which projects can qualify, including strict monitoring under the auspices of a third party, Carbon Market Watch. The first credits under the new mechanism are expected to be granted in 2026.

Carbon pricing has, for many, been the Holy Grail climate solution that has never quite lived up to its promise. But its day may finally have come. The European Union has been the global leader in this field, with a cap-and-trade Emission Trading System that has played a key role in its transition to clean energy. Now, the EU is implementing a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), setting a tariff on imported products that are highly carbon intensive. But CBAM can be avoided if the exporting country has its own comparable carbon price. So in response, no fewer than six countries – India, Brazil, Indonesia, Turkey, Vietnam and Argentina – are launching their own pricing programs. After all, why pay Europe when you can collect a carbon tax and use the funds domestically?

So this might be the best news of the year. One leading group of nations got carbon pricing to work through a cap-and-trade approach – and in response, we see six countries comprising more than a quarter of the world’s population following suit. The United Kingdom and China are also implementing carbon pricing, and Canada’s program, once confined to individual regions, now has national scope.

We know who is missing from this picture. The US had its chance to exert global leadership on climate change, but that opportunity is gone, perhaps permanently. We see, however, that the world moves ahead notwithstanding our abdication, and that is where much of our hope must rest for now. The accumulating damage to the national interest will not be easily repaired.