This Fall, the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality released an apparently routine notice requesting comments on a proposal to sell ethanol into the state. Like everywhere in the US, almost all commercial gasoline in Oregon is blended with 10-15% ethanol to raise the octane level and (according to the Department of Energy) improve “drivability.” The proposal from Red Tail Energy LLC was made under Oregon’s Clean Fuels Program, a law allowing fuel suppliers to earn monetizable credits by offering low-carbon fuels that displace fossil oil and natural gas. Of particular interest was the fact that RTE already sells ethanol into Oregon under the program, making a tidy profit by producing and delivering the fuel with a 40% decrease in lifecycle carbon dioxide emissions compared to gasoline made from crude oil. Now, the company is asking the Oregon DEQ to approve a new manufacturing plan that eliminates half of the still-remaining emissions (and earns even more credits) by capturing the CO2 emitted from its North Dakota ethanol fermentation plant. RTE is able to inject the recovered CO2 into subterranean pores of the adjacent Broom Creek geologic formation, where it should remain sequestered for hundreds to thousands of years, if not longer.

This is the first proposed Oregon clean fuels pathway to incorporate carbon capture and storage (CCS), and it will certainly offer an example for ethanol production with CCS by other manufacturers – who can also sell their low-carbon product into similar Clean Fuels Programs in California and Washington state. Remaining lifecycle emissions come primarily from growing and harvesting the corn feedstock, and from delivering the finished product, mostly by rail, to markets on the West Coast and elsewhere. The ethanol fermentation process is particularly well-suited to carbon capture, with nearly 100% of the emerging CO2 efficiently retained by chemical scrubbers in the smokestacks. Given the generous federal tax credit for CCS on top of the state subsidies, we can be confident that many more manufacturers will follow suit – at least until EV’s fully replace the cars and light-duty trucks that run on gasoline.

Ethanol fermentation plants are just one of many venues for CCS, which is finally showing signs of emerging from many years in the doldrums. In its Global Status of CCS 2023 report released last month, the Global CCS Institute documents a very large increase in the CO2 capture capacity of CCS facilities now in planning or construction stages, with the US by far the world leader. Unlike the great majority of CCS operations so far, which use the captured CO2 to enhance oil recovery (EOR) from depleted wells (with little or no climate benefit), most of the 26 projects now under construction around the world will, like the RTE plant, sequester the carbon in dedicated geologic reservoirs. Hundreds of other projects still in the planning stages, including more than 100 in the US, similarly envision permanent burial of the captured carbon in underground formations.

The recent uptick in CCS is driven by the Inflation Reduction Act’s tax credits in the US, and by similar public subsidies in many other countries. The global targets of 1 gigaton (Gt) of buried CO2 per year by 2030 and 10 Gt/year by 2050, as envisioned in net zero emissions roadmaps, still seem to many like a distant pipe dream given that operational global capture capacity is now only 0.05 Gt/year – with most of that dedicated to EOR. Nonetheless, RTE, another US ethanol project operated by Archer Daniels Midland, and a number of other projects around the world have been able to demonstrate safe and (so far) permanent storage of the CO2, which mineralizes when injected at depths of one kilometer or more. The Environmental Protection Agency’s review of RTE’s monitoring, reporting and verification plan thoroughly documents the company’s plans for monitoring CO2 leakage and induced seismicity, its implementation of safety measures required under the federal Safe Drinking Water Act, and the favorable geologic characteristics of the Broom Creek formation. Such a rigorous review process would seem to bode well for increasing public confidence in the CCS industry.

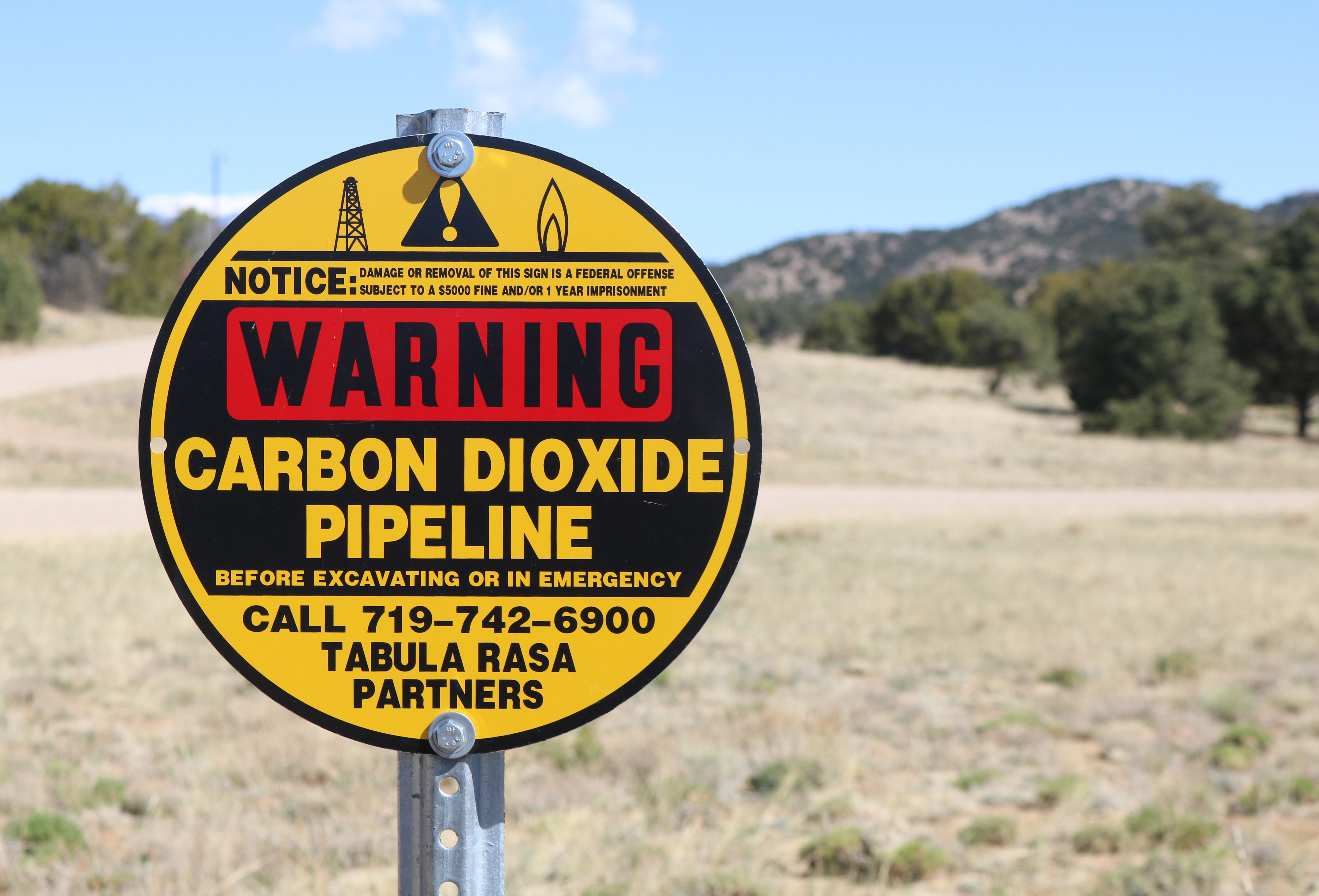

RTE’s ethanol fermentation plant is situated directly on the Broom Creek formation, and the captured CO2 only needs to be transported two miles to the injection well. Such a happy circumstance, though, is far more likely to be the exception than the rule. Much of the time, pipelines will be required to transport the CO2 from capture points to injection sites. The CCS Institute’s list of over 100 planned CO2 capture facilities in the US might be just the tip of the iceberg, considering that the technology can be applied in power generation, petroleum refining, ethanol fermentation, fertilizer plants, petrochemical facilities, steelmaking plants, cement manufacturing and more. Indeed, independent analyses from the Great Plains Institute and the Princeton Net Zero America team suggest that the 5000 miles of existing CO2-dedicated pipeline will likely need to be expanded by ten-fold or more to meet the US sequestration target of 0.9-1.7 Gt/year by mid-century.

No fewer than three million miles of natural gas pipelines exists in the US today, so adding another 50,000 or even 100,000 miles of dedicated CO2 pipeline to facilitate CCS does not seem like a big stretch. The new infrastructure would also support direct CO2 capture from the atmosphere, if that technology becomes feasible at scale in the next few decades. At least a good start at funding for new pipelines has already been secured as part of the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, sometimes known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. The BIL appropriates about $2 billion for low interest loans and grants for CO2 pipeline construction, which would go to private companies interested to build the pipelines. Four of the seven recently awarded billion-dollar Hydrogen Hub grants under the BIL involve making hydrogen from natural gas feedstocks, and thus also implicate CCS and a need for CO2 pipelines. Many of the proposed new CCS projects involving ethanol fermentation and other manufacturing technologies are located in the Midwest, a region now clearly emerging as a CO2 infrastructure hub.

Fans of industrial policy and technological solutions to the climate crisis can find much to cheer about here, but others are warning that all is not rosy. In February of 2020, a CO2 pipeline rupture in Satartia, Mississippi generated a low-lying blanket of the gas, which is 50% heavier than air and can take considerable time to disperse. Forty-five people were hospitalized with various degrees of disorientation and asphyxiation caused by displacement of breathable oxygen, some with symptoms that have persisted for years. The rupture was a bellwether event, alerting concerned citizens and advocacy groups to the consequences that a new national-scale network of crisscrossing pipelines would have for human health, the environment, and landowner interests.

Summit Carbon Solutions is among the companies leading the nascent buildout of CO2 pipeline infrastructure in the Midwest. Interviewed in May of this year by Oregon Public Broadcasting, its regulatory director, John Satterfield, blamed the 2020 Mississippi incident on lax safety procedures by the pipeline operator, Denbury Gulf Coast Pipelines. Mr. Satterfield went on to emphasize the reliability of the technology that will be used to build the new pipelines, commenting further that there are no “huge gap[s] in the regulatory schema.”

That statement is questionable. In fact, while the federal Pipeline Safety Act does generally authorize the Pipeline Hazardous Materials and Safety Administration to regulate CO2 pipelines, existing rules only cover CO2 piped in the high-pressure supercritical state needed for EOR. This is not adequate for CCS applications, where transport as a gas or cooled liquid under moderate pressure is also possible. A detailed study commissioned by the advocacy group Pipeline Safety Trust revealed that CO2 pipeline regulations have not been updated in more than three decades, and that the PHMSA agency failed to write new rules covering gas or liquid states of CO2 even after being required to do so in a 2011 law passed by Congress. As the study puts it, this regulatory vacuum creates the possibility that a clever pipeline operator might be able to avoid any federal oversight at all.

Fortunately, the 2020 Mississippi pipeline rupture and political pressure exerted by Pipeline Safety Trust and other advocacy groups is having a beneficial effect. Last year, the PHMSA announced that it would strengthen its safety oversight of all CO2 pipelines, and would start writing new rules, expected in 2024, to address the regulatory gaps. In a letter sent last month, Pipeline Safety Trust and 30 cosigning groups urged PHMSA to address the safety concerns laid out in the detailed study. These include strict restrictions on dangerous contaminants such as water and hydrogen sulfide, requirements for strengthening the physical structure of pipelines, information on terrain-specific dispersion of the heavy CO2 in the event of breakages, and leak detection and repair. Congress is also getting into the act with a new bipartisan bill, the PIPES Act. Introduced just last week, the bill is needed for reauthorizing the PHMSA, but also represents an opportunity for lawmakers to offer the agency direction on safety and other issues. These might well include CO2 pipeline siting, which is presently in the hands of the states and lacks any coherent national plan. Given the BIL funding for pipelines and projected CCS buildout across many industries, this is clearly a propitious moment for Congress to act.

___________________________________

https://www.oregon.gov/deq/ghgp/cfp/Pages/default.aspx

https://www.oregon.gov/deq/ghgp/cfp/pages/clean-fuel-pathways.aspx

https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2022-04/rtemrvplan.pdf

https://www.epa.gov/uic/class-vi-wells-used-geologic-sequestration-carbon-dioxide/

https://www.whitecase.com/insight-alert/hydrogen-hub-projects-awarded-7-billion-us-department-energy

https://www.opb.org/article/2023/05/21/us-co2-pipelines-poisoned-town-wants-you-to-know-its-story/

https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/49/60102

https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-49/subtitle-B/chapter-I/subchapter-D/part-195

https://pstrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/3-23-22-Final-Accufacts-CO2-Pipeline-Report2.pdf

https://pstrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/PR-CO2-Sign-On-Letter-11.21223-_FINAL.pdf

https://transportation.house.gov/news/documentsingle.aspx?DocumentID=406985